As mentioned in a previous post, correspondence from Harold Norse is included in an exhibit at the John Rylands Library in Manchester, England. Off Beat: Jeff Nuttall and the International Underground features material from the archive of British writer and publisher Jeff Nuttall. His mimeo publication My Own Mag was one of the few outlets that published William Burroughs most experimental Cut Up work of the 1960s.

As mentioned in a previous post, correspondence from Harold Norse is included in an exhibit at the John Rylands Library in Manchester, England. Off Beat: Jeff Nuttall and the International Underground features material from the archive of British writer and publisher Jeff Nuttall. His mimeo publication My Own Mag was one of the few outlets that published William Burroughs most experimental Cut Up work of the 1960s.

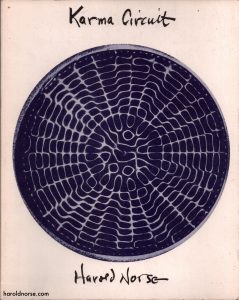

The letter from Norse to Nuttall was written sometime in 1968, shortly before his repatriation to America following fifteen years abroad. At that time, Norse was living in Regents Park, London, attempting to recover from chronic hepatitis and a broken love affair while busy with the publication of his collection Karma Circuit.

The letter from Norse to Nuttall was written sometime in 1968, shortly before his repatriation to America following fifteen years abroad. At that time, Norse was living in Regents Park, London, attempting to recover from chronic hepatitis and a broken love affair while busy with the publication of his collection Karma Circuit.

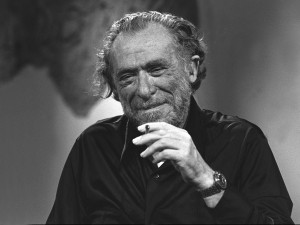

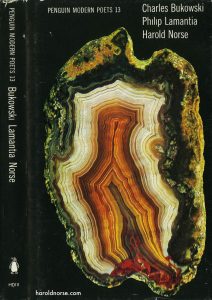

He was also editing an edition of the Penguin Modern Poets Series No. 13 featuring himself, Philip Lamantia and Charles Bukowski, in one of the L.A. poet’s first big exposures outside the small press. William Burroughs, who lived near by on Duke Street, St. James, was hooked on Scientology, offered to analyze Norse with the help of an e-meter and two tin cans.

The letter opens “after the debacle, i.e. anglo-american poetry conference at the American Embassy.” (I am not aware of the conference Harold’s referencing. If any readers have information, please post a comment.)

The letter opens “after the debacle, i.e. anglo-american poetry conference at the American Embassy.” (I am not aware of the conference Harold’s referencing. If any readers have information, please post a comment.)

Harold continues to set the scene: “doors guarded by US Marines–don’t worry, boys, poetry ain’t dangerous here.” A nodding of his head is misread by the poet Edward Lucie-Smith as an agreement with (I assume) Nuttall’s presentation, “but actually was beating time to a tune by that great modern poet, Dylan,––Bob Dylan:

“Something is happening here, but you don’t know what it is, Do you, Mister Jooones…”

The reference to “that great modern poet” is a bit tongue-in-cheek as Norse had befriended Welsh poet Dylan Thomas back in New York City in the early 1950s.

From there the letter takes off into freestyle musings of 20th century poetry and arts that is unmistakably Norse, infused with his keen awareness of history which, towards the letter’s closing, connects to the present state of poetics:

& my mind went back to the Cabaret Voltaire (1916) where Hugo Ball chanted nonsense syllables, the Odéon where Tzara, at the end of the world, picked out words from a hat…& knew where it was at…& Gertrude Stein knew, & Ezra knew, & the poet of Finnegans Wake knew…& even Eliot knew but twisted it all back into the hands of the rational boys, who took fright and crept all the way back into the lap of Madame Bovary, as if 2 wars hadn’t happened, as if it wasn’t happening now everywhere…

You can click on the photo of the letter’s display above to view the text in better detail.

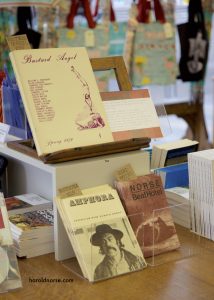

The exhibit, which runs through March 5th, is free and the Rylands Library is open every day. While you’re there, make sure to browse through their excellent gift shop or purchase a beverage from their drink bar. Several of Norse’s books are in stock, a rare chance for UK bibliophiles to obtain these pristine, out-of-print copies.

The exhibit, which runs through March 5th, is free and the Rylands Library is open every day. While you’re there, make sure to browse through their excellent gift shop or purchase a beverage from their drink bar. Several of Norse’s books are in stock, a rare chance for UK bibliophiles to obtain these pristine, out-of-print copies.

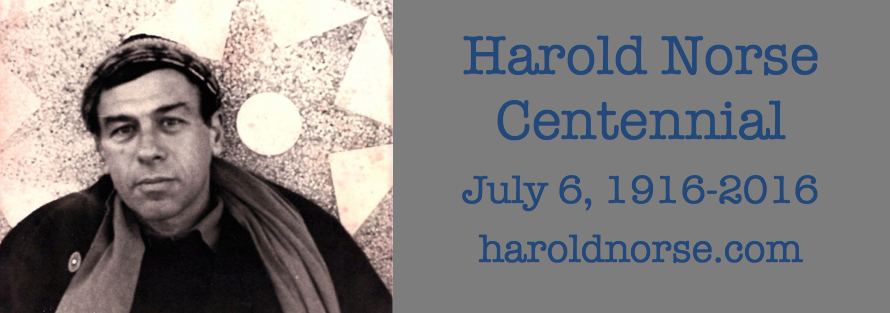

Following the remarks in the letter to Jeff Nuttall, it’s a good time to begin reviewing last summer’s fantastic series of events commemorating Harold Norse’s 100th birthday. It’s no mere coincidence that the Bastard Angel of Brooklyn was born the same year as Hugo Ball, Tristan Tzara and others birthed the revolutionary art movement DaDa in Zurich, Switzerland.

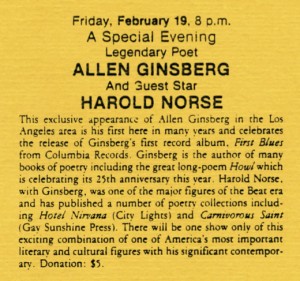

The second centennial celebration was held at the Beat Museum that has, for over a decade, offered an invaluable resource in preserving and sharing the legacy of the Beat generation. It was also the host of Harold’s last public poetry readings.

The second centennial celebration was held at the Beat Museum that has, for over a decade, offered an invaluable resource in preserving and sharing the legacy of the Beat generation. It was also the host of Harold’s last public poetry readings.

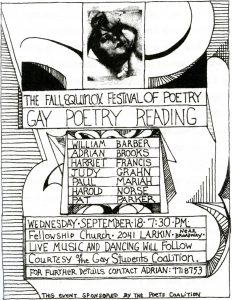

Upcoming posts will explore the evening’s other participants. For now the focus is on remarks made by poet & writer Adrian Brooks, featured in a previous post, who was introduced to Harold in the early 1970s through poet Gerard Malanga. The two developed a friendship that encompassed Brooks assisting with Bastard Angel magazine as well as participating in Norse’s Master Class taught to a select group of young writers.

After reading a brilliant poem about Harold composed specifically for the event, Adrian joined in adding his comments to questions about various aspects of Harold from poet to scholar to teacher. This post will close with quotes from Adrian’s reflections from that evening which presciently expand upon observations made in Harold’s letter from the Rylands exhibition.

In addition to wanting his own place in the pantheon of modern “greats,” I don’t think it was just his nurturing that was at play. Harold was alive and therefore life spoke to him through the most haphazard signals.

I think he had a tremendous sense of dislocation that any artist has–a loneliness, a haunted-ness–because he had a great heart.

There’s so much to say. He was never spiritually disciplined, but he absolutely got it. I think if Harold were here tonight, aside from being very pleased that this event was happening, he would also want to connect what’s happening here tonight in honor of him, to what’s happening in this country right now, with the killing of black people and the schism which he saw so clearly. Not only racially and through the lens of having been an expatriate, but really wanting the country to come together and embrace a larger sense of humanity.

He felt chiseled out of that because most artists are. But if he had a spirituality, it was in the recognition of the place of artists and writers in other countries, like Cavafy, or the other people he translated, and people he knew, Anaïs Nin, for example.

He felt chiseled out of that because most artists are. But if he had a spirituality, it was in the recognition of the place of artists and writers in other countries, like Cavafy, or the other people he translated, and people he knew, Anaïs Nin, for example.

He was also propelled by a larger sense of justice. Partly because he had been denied it as a child, and a child who is denied justice either is destroyed by it or fights and Harold was a fighter. He was gutsy.

I feel like we are living, right now, in a catastrophe, which Harold saw and forecast and was right about, even though he missed the ‘60s here. That caused a kind of syncopation in his sense of contact with America. So partly through nurturing young writers, Neeli [Cherkovski] is a perfect example, I guess I am, he created this Master Class and it was a phenomenal experience.

[Audience question as to what was Harold’s focus like.]

When I was listening to the other people [speaking tonight] I was thinking about that. Probably what I am going to say may be offensive, but you asked a question, so I am going to tell you what I think.

I think the two great themes for an artist are sex and death. I think Harold’s focus was sex not death, but I think it wasn’t really sex that was his focus. It was the yearning for love, although he wrote that poem “Friends, if you wish to survive I would not recommend” it.

I think he had a very ambivalent relationship to desire. Harold was friends with Tennessee Williams before Williams was famous. They were in Provincetown together the summer that Williams wrote The Glass Menagerie. I think of desire– sex– like it’s presented in A Streetcar Named Desire; the opposite of death is desire. But for Harold I think it was the attempt to staunch a wound through the enacting of sex.

That’s why I think there is very little of the “other” in his work. It’s about him and his relationship to it, not another person. Rarely, is there another person in his work. I don’t think that diminishes his art, but when you look at the plight of the homosexual, that Harold was born into and grew up with in America, it was so dangerous to be gay, so challenging to try to be a man, because he was a man, against the odds. He was a short man, a Jewish man, a poor man; the odds were stacked against him. Yet there was a grandness in him.

Once again the host of this event

Once again the host of this event