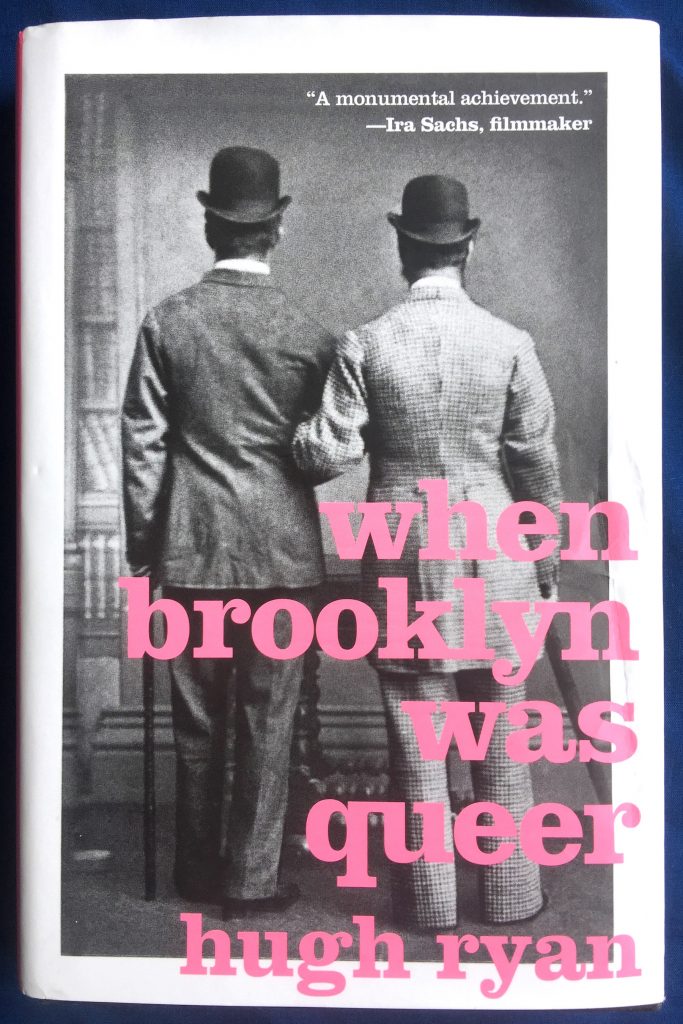

As today marks the 103rd birthday of the Bastard Angel of Brooklyn, poet Harold Norse, a fantastic new book about the queer history of the New York City borough highlights Harold’s connection to his hometown during his formative years. I had the chance to speak with the author of When Brooklyn Was Queer, historian and writer Hugh Ryan, about his work.

Ryan has stated that when he moved to Brooklyn, he was surprised to discover its local library didn’t have a book that focused on the neighborhood’s queer history, so he set out to write one. When Brooklyn Was Queer is a monumental contribution to growing history of the varied and still little-known experiences of queer people before the advent of the modern gay rights movement.

Among the parts I found most significant about this book is the attention Ryan paid to experiences of gender non-conforming individuals and African-American women. Historically these voices have remained obscured, a reality compounded by the lack of traditional archive resources like photographs, correspondence and diaries. So it was that Hugh had to turn to sources such as newspapers, medical journals and police reports which were written by men who viewed queer people through the lens of criminality or mental illness– a fact that’s still too common in communities dominated by religious fundamentalism. I asked Hugh about the particular challenge.

I think I often had to sit with what was written on the page and, knowing it came from a very biased source, ask myself how were there other ways this scene could have been interpreted from someone else’s point of view. I can only work from the information I have, but can I try to unwind some of the assumptions that were made by these doctors and lawyers and judges? It does take a while and you have to read the things over and over again. For me what was important was highlighting the fact that I was doing that and why I was doing that, so anyone reading that could make their own decision about what I had decided. I didn’t want anyone to think I was making assumptions I couldn’t prove, but more to show possibility than a definite answer.

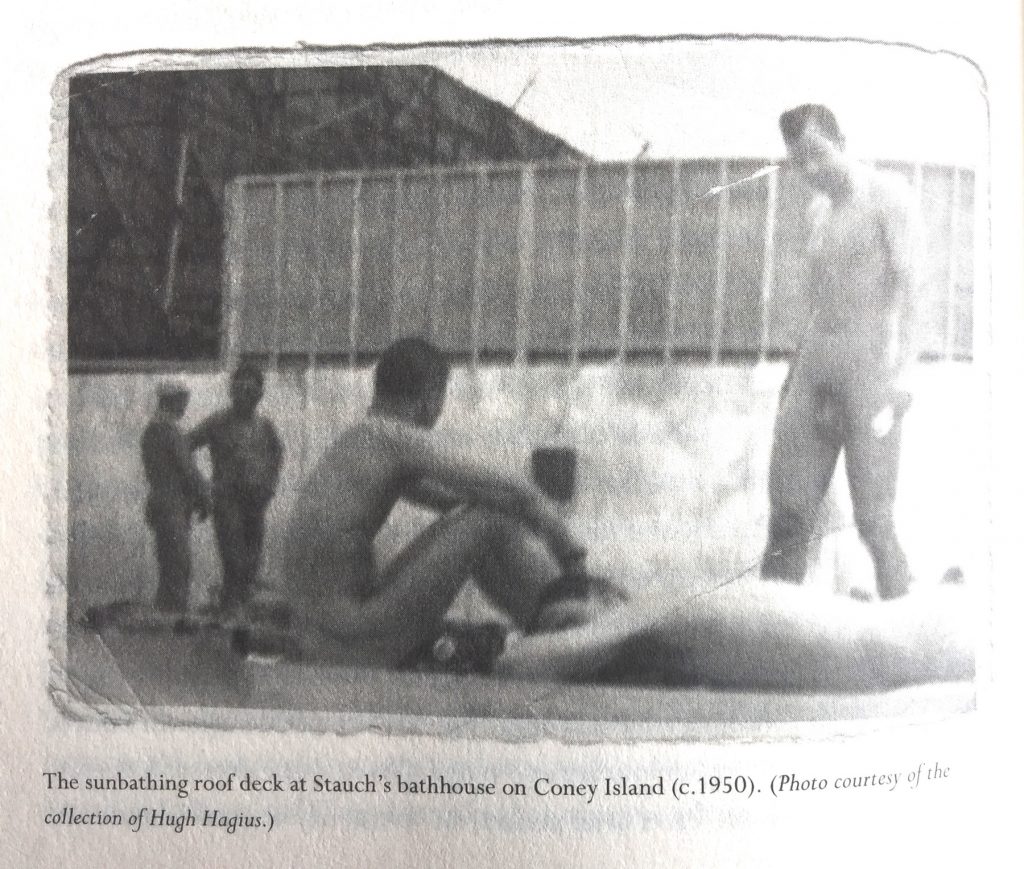

One particularly fascinating story features a young white trans women who went by the name Loop-the Loop after the popular Coney Island roller coaster. This glimpse into her story came from interviews given to a racist medical doctor whose report on Loop-the-Loop was published under the headline “The Biography of a Passive Pederast.”

This offensive report was part of the early twentieth-century eugenics movements which saw social problems as a result of unnatural behavior and genetics of those who weren’t white, heterosexual and Christian. Such psuedo-legitimacy of bigotry under the guise of medical science is a core feature of white supremacy.

Despite the doctor’s biased lens, Loop-the-Loop offers an interesting look into her world. She comes across as not only accepting of herself but defiantly comfortable with her sexuality. As an orphan without education, she worked as a prostitute on the Brooklyn streets around the time that Harold Norse was born.

Two of Harold’s early poetic inspirations Walt Whitman and Hart Crane are also prominently featured in the book, in particular their experiences around Brooklyn’s waterfront which was a site of teeming same-sex and gender nonconforming activity until its demise following World War II. Whitman and Crane had in common a poetry steeped in a mystical voice, one that was unabashedly romantic. Both poets offered Harold, born out of wedlock to an illiterate immigrant, an example of the transformative power of poetry and it was in their footsteps that he began not only to write poems but see himself as a poet.

Though today’s younger readers may struggle to appreciate Whitman’s work, particularly his exaltation of a uniquely American ideal, the issue of his sexuality is still challenging people’s assumptions about sexuality. As Ryan related to me when he was asked by a publication to create a list of 25 queer books that people should read during Pride month.

I included Walt Whitman on it. The editor said, “You should say something there about how there’s debate about his sexuality and no one’s sure that he’s [gay]– and I said,” Nope, there’s no debate. I’m not writing that.” She took it very well. She said, “I had no idea. It was in high school…” I said, “Yep, we all learned some version of that in high school.” It’s so much about getting this information out into the world so it’s easier for people to find it even if they are not taught it in school.

There’s a great deal to write about Harold Norse and Brooklyn but Ryan’s focus is on Harold when he was a student at Brooklyn College. The school had opened at the start of the Great Depression to offer a free education for all city high school graduates. Harold’s gift for language was quickly recognized and he soon became editor of the college literary magazine. It was at this time that he became friends and eventual lovers with another young Jewish boy named Chester Kallman. Harold would often reminisce about Chester as the great love of his love, though their relationship became contentious as Chester turned his attention to his the poet W.H. Auden with whom he became life long partners.

Brooklyn College was also significant in that it gave Harold his first sexual experience with another man thanks to his English-literature professor David McKelvey White. Harold’s version of the story is included in his autobiography Memoirs of a Bastard Angel, though Ryan’s book provides previously unknown information about David McKelvey White.

The son of the governor of Ohio, White grew up well-to-do and well educated. He was outspoken in his sexuality at the time as well as a member of the American Communist Party. He lived openly with his boyfriend who was also a Party member and a professor at Brooklyn College. It was White’s egalitarian politics, accentuated by the radicalism of the day, which led him to a teaching position less illustrious than what his patrician family would’ve hoped for. His time at the school was not long as White eventually left midsemster for Spain and joined the Loyalists as a machine gunner fighting against the fascist forces of General Francisco Franco. Upon his return to the U.S.A. two years later, Brooklyn College refused to rehire him. He eventually took him own life in 1945.

Harold’s recollections of David McKelvey White show a man of great intellect and sensitivity and Harold enjoyed the attention of the older professor, who exposed him to art and culture and took him for swimming and fine meals at Brooklyn’s posh St. George Hotel. Even the story of Harold’s deflowering is one of an old school gentleman without the exploitive or predatory aspect that has come under widespread criticism in our era of the #MeToo movement.

Given that Harold and many of his friends who were also gay writers, such as William Burroughs, Allen Ginsberg, Charles Henri Ford, were known for their intimate relations with underage boys, I asked Ryan about how their experiences could co-exist with today’s changing views.

They lived in a very different time where people who understood their sexuality found each other at much younger ages, in certain ways the only people you could find when older where younger. It wasn’t like there were there were the gay storylines or knowledge there is today. I do think there’s a common part of the queer history that’s fallen out a little bit today.

I think it’s important that these things happened and this is what we know and learned from them, this is the experiences of these people. They don’t necessarily correlate with things today. We don’t know if Harold were a young person today whether he would end up with David McKelvey White. That’s impossible to know and I think it’s best to let them speak about their experiences and trust them as much as possible when Harold said it was a great experience for him.

Unfortunately my phone conversation with Hugh Ryan was cut short by a sudden rainstorm that’s a hallmark of summertime in New York City so we were unable to talk more, especially about Harold’s relationship with Auden whose connection to Brooklyn continued with the esteemed English poet’s residency at 7 Middagh Street which became a short lived queer arts commune. Known as the “February House” due to the winter birthdays of a number of it’s illustrious inhabitants that included writer Carson McCullers and composer Benjamin Britten and ballet and theater designer Oliver Smith.

Though you can learn more about their story and the vibrant, relevant queer history in When Brooklyn Was Queer available from St. Martin’s Press. Ryan’s next book will take a look at the Women’s House of Detention which used to be located in Manhattan’s Greenwich Village neighborhood whose inmates included Dorothy Day, Angela Davis and Harold’s good friend the poet and actress Judith Malina.

I know how much Harold would have loved reading Ryan’s book, not only appreciating the coverage of his own story but also the uncovering of hidden histories. There’s still so much to learn about the queer experience of the past and how it can contribute to the struggles we still face today.

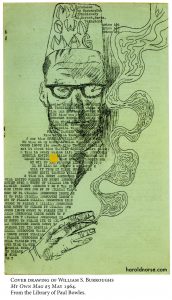

A new anthology features an essay on the visual artwork created in the early 1960s when expatriate writers were living in Paris at the

A new anthology features an essay on the visual artwork created in the early 1960s when expatriate writers were living in Paris at the

An essay co-authored by myself and my brother Tate, of

An essay co-authored by myself and my brother Tate, of

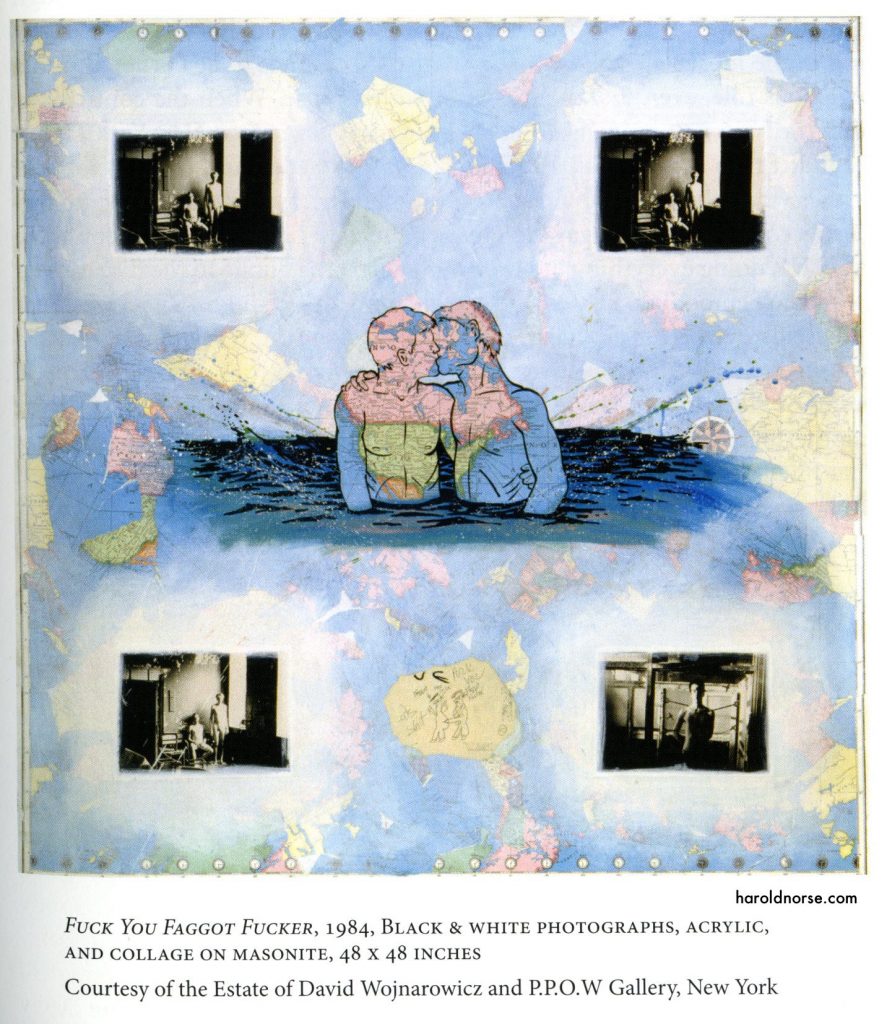

One artist I was surprised to not know of is Ben Morea, considering his early alliance with Allen Ginsberg,

One artist I was surprised to not know of is Ben Morea, considering his early alliance with Allen Ginsberg,

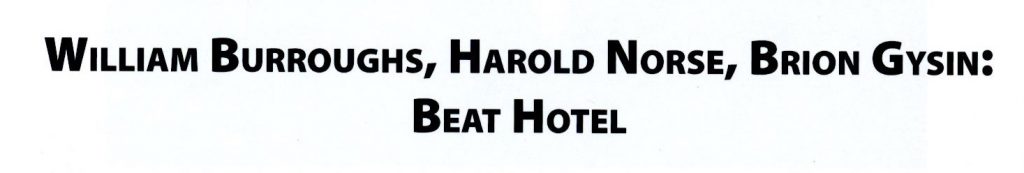

Among the anthology’s most extensive essays are those about writer, artist and filmmaker

Among the anthology’s most extensive essays are those about writer, artist and filmmaker

As relayed in his Memoirs of a Bastard Angel, Harold acted as a mentor for a then unknown Canadian folk singer named Leonard Cohen. He was inspired to write after reading Norse’s “Sniffing Keyholes” which made a big impression on the young writer.

As relayed in his Memoirs of a Bastard Angel, Harold acted as a mentor for a then unknown Canadian folk singer named Leonard Cohen. He was inspired to write after reading Norse’s “Sniffing Keyholes” which made a big impression on the young writer. My extensive essay “Harold Norse– the Bastard Angel of Brooklyn” has just been posted to Beatdom. You can read it

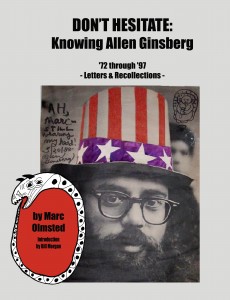

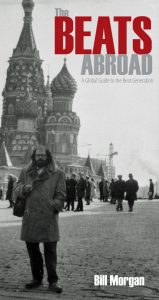

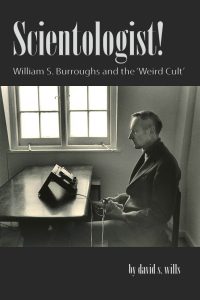

My extensive essay “Harold Norse– the Bastard Angel of Brooklyn” has just been posted to Beatdom. You can read it  In addition to posting online essays, Beatdom publishes an annual literary journal as well as operating its own press. Some of the titles include Wills’

In addition to posting online essays, Beatdom publishes an annual literary journal as well as operating its own press. Some of the titles include Wills’