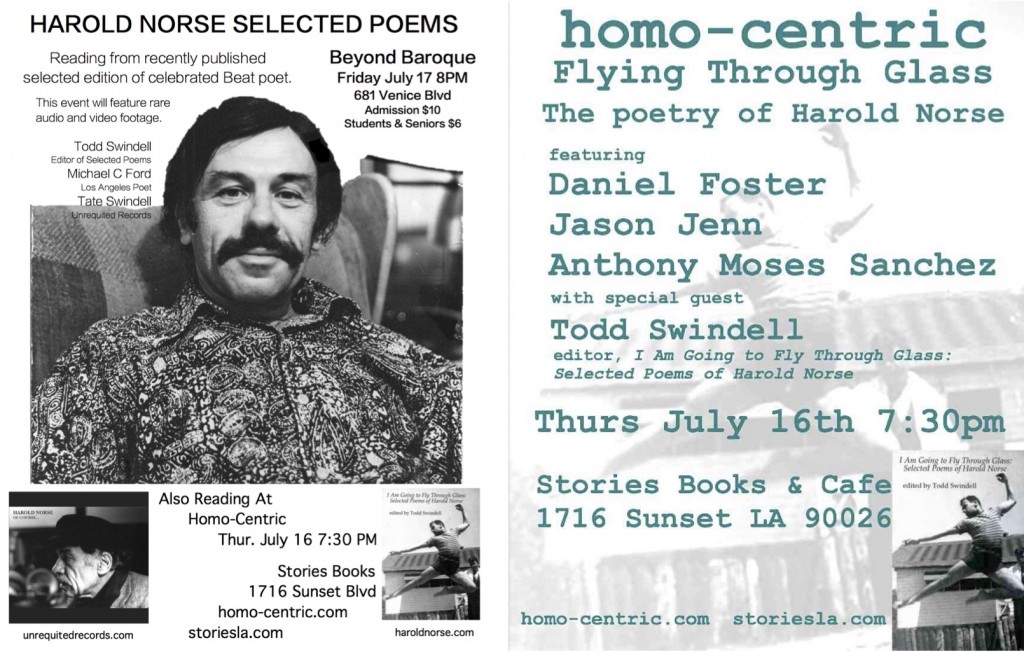

In anticipation of two Harold Norse poetry readings happening next week in Los Angeles, let’s take a look back at Harold’s time in living in Venice Beach. After traveling for 15 years in Europe and North Africa, Harold returned to the West Coast in the summer of 1968. America had changed a great deal during his absence and Harold’s attention began to focus on environmental destruction and the blossoming of gay liberation.

In anticipation of two Harold Norse poetry readings happening next week in Los Angeles, let’s take a look back at Harold’s time in living in Venice Beach. After traveling for 15 years in Europe and North Africa, Harold returned to the West Coast in the summer of 1968. America had changed a great deal during his absence and Harold’s attention began to focus on environmental destruction and the blossoming of gay liberation.

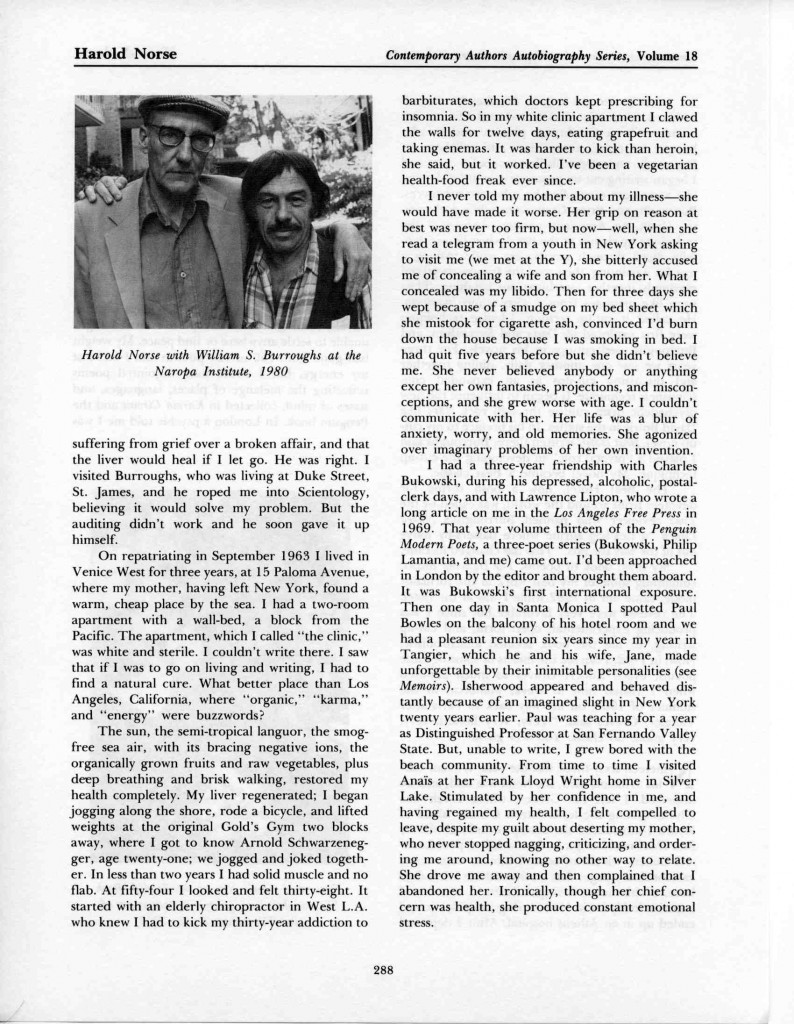

To recuperate from a debilitating hepatitis infection, a significant factor in his repatriation, Harold became a lifelong vegetarian and started lifting weights with Arnold Schwarzenegger at the world famous Gold’s Gym. He also availed himself of friendships with other writers then residing in Los Angeles. Among them, old friends who were teaching at universities like poet Jack Hirschman, who had met Harold in 1965 on the island of Hydra, and the writer Paul Bowles, whom Harold knew from his time in Tangier.

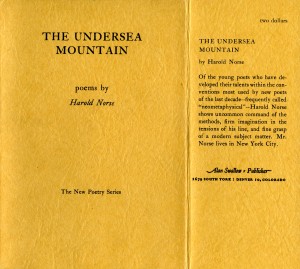

The writer Anaïs Nin first recognized Harold as rising talent in New York in the summer of 1953. In Harold’s must-read autobiography, Memoirs of a Bastard Angel, he recounts an evening at her Greenwich Village penthouse apartment on West Thirteenth Street. When, during the evening, she produced a copy of Harold’s first book of poems, The Undersea Mountain, and her praised continued. “You have an extraordinary power to express feeling by breaking down the barriers that surround it,” she told him. “It is very rare, especially in America. Americans are afraid of feeling, or expressing it. You do it wonderfully.”

The writer Anaïs Nin first recognized Harold as rising talent in New York in the summer of 1953. In Harold’s must-read autobiography, Memoirs of a Bastard Angel, he recounts an evening at her Greenwich Village penthouse apartment on West Thirteenth Street. When, during the evening, she produced a copy of Harold’s first book of poems, The Undersea Mountain, and her praised continued. “You have an extraordinary power to express feeling by breaking down the barriers that surround it,” she told him. “It is very rare, especially in America. Americans are afraid of feeling, or expressing it. You do it wonderfully.”

Their connection continued during Harold’s time in Venice as he recounts further on in Memoirs of a Bastard Angel:

“Occasionally I visited Anaïs Nin in Silver Lake, a suburb of Los Angeles, where she lived in a Frank Lloyd Wright House with Rupert Pole, the stepson of a great architect. It was a wonderful house made of boulders, with a spacious living room; it felt alive, like an animal—a living room, Anaïs suggested I submit a new volume of poems to New York publishing houses and compile a list of comments on my work from established authors, which I did, quoting Baldwin, William Carlos Williams, Robert Graves, Ginsberg and others. It made me feel like a venerable Old Master. When I told here that Robert Giroux of Farrar, Straus & Giroux had described the volume as “raw meat” poetry, “although,” he added, “the poems are magnificent,” she was indignant. “That is absolutely untrue,” she said, “your poetry is racé!”

Giroux had used Robert Lowell’s designation for Ginsberg’s poetry. At the same time poetry fell into neatly under two labels: “raw meat” or “cooked meat.” I held that cooking deprived food of all its life-giving nourishment. In 1970, however, the major publishers still got indigestion from Beat, raw-meat writing. Today it has become kosher. “They never had faith in me,” said Anaïs as I looked out of the window at a cat with a live bird in its mouth. “My French publisher still can’t believe that my Diaries are a best-seller in France, where I have won prizes for it. Harcourt, Brace published only twenty-five hundred copies of the first printing. So I know how you must feel when they turn you down.””

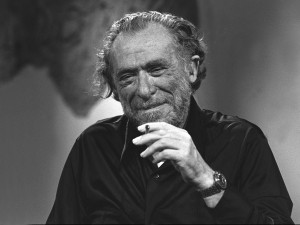

Harold and Charles Bukowski had begun a correspondence in the late 1960s. Their letters were collected for publication by Harold in the late 1990s under the title Fly Like a Bat Out of Hell and was meant to be published by Thunder’s Mouth Press following the release of his Collected Poems in 2003. The letters remain unique among the volume of Bukowski material that continues to be published.

In his correspondence with Norse, Bukowski emerges as a still struggling writer finding inspiration and comradeship from the Brooklyn born poet- now exiled. At that time, Harold was near death from hepatitis which charged his writing with the raw directness of the poet struggling to survive. Continuing from his Memoirs of a Bastard Angel: