“In this selection, Swindell shows how Norse broke new ground through his open exploration of gay identity and sexuality using accessible language in what he referred to as a new rhythm – the voice of the street. Humor, compassion and inner pain are all to be found in equal measure.”

That’s an excerpt from a new review recently published in the online poetry review GALATEA RESURRECTS (A POETRY ENGAGEMENT) of my selected edition of Harold Norse’s poetry. The complete review can be read at this link.

That’s an excerpt from a new review recently published in the online poetry review GALATEA RESURRECTS (A POETRY ENGAGEMENT) of my selected edition of Harold Norse’s poetry. The complete review can be read at this link.

Written by Scottish based author Neil Leadbeater, who has read the Brooklyn born poet for nearly fifty years, this excellent review offers a perceptive appreciation of Norse’s vital yet overlooked role in composing poems that were “raw and straight to the point.”

“For too long, Norse has been the outsider, certainly in the U.K., but, with this publication, the “lone wolf”, as he once described himself, has finally come in from the cold.”

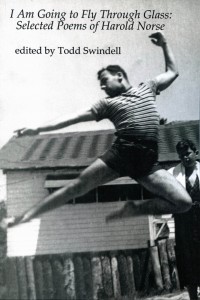

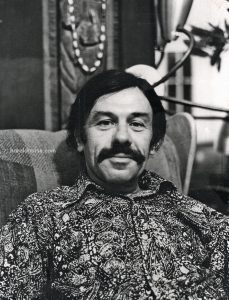

I Am Going to Fly Through Glass: Selected Poems of Harold Norse was published in 2014 by Talisman House and is the first posthumous publications of Norse’s influential poetry. Illustrated with photographs of the poet, it includes selections from over sixty years of Norse’s work. Thanks to Neil and GALATEA RESURRECTS for helping more readers become aware of this accessible introduction to the poetry of Harold Norse. Here are a few more excerpts:

“The present selection goes a long way towards putting Norse back on the poetical map, especially for readers in the U.K. A helpful preface by Todd Swindell and an informative introduction by Neeli Cherkovski helps to place Norse and his colorful life in context by establishing the background to his work and its relationship to the rest of the beat movement in America.”

“He could write a protest poem that was the equal of any by Ginsberg…which reveal his engagement with politics and his concern for the environment as well as his commitment to poetry as a vehicle of persuasion to help bring about a better world.”

Continuing from the previous post about the Beat Museum’s Norse Centennial Celebration, here are more excerpts from comments made by poet & writer Adrian Brooks who was a friend of Harold’s. As writer & editor Raymond Foye wrote in the comments section, Brooks reflections offer “a beautiful appreciation of Harold Norse, and perfectly evokes his generous spirit. How marvelous to see his personality presented in the context of his work. He is one for the ages.” I couldn’t agree more.

Todd: I was wondering, Adrian, if you wanted to talk about your experiences with Harold producing Bastard Angel magazine? People are always interested in how Harold was publishing older poets like Kerouac, Di Prima and Corso and then new poets like yourself, Neeli Cherkovski, Andrei Codrescu, Erika Horn. A theme that came up was it wasn’t just who Harold had known, it was always current and melding the past and the present.

Adrian: What am I supposed to say?

Todd: [To Audience] Harold also had a Master Class for young writers when he came back to the United States. Harold was not only a writer; he was also a very good teacher. [To Adrian] So this sense of being able to work with younger poets, bringing the past into the present, but also seemed to be a contemporary in a way. Am I wrong?

Todd: [To Audience] Harold also had a Master Class for young writers when he came back to the United States. Harold was not only a writer; he was also a very good teacher. [To Adrian] So this sense of being able to work with younger poets, bringing the past into the present, but also seemed to be a contemporary in a way. Am I wrong?

Adrian: Harold was complex. There’s that phrase in Whitman, “multiplicity of selves.” He was too complex to say that he was this, and this, and this. It wasn’t that. [Long pause]

His apartment was a mess of manuscripts. People were sending him lots of things because he was publishing a magazine and they wanted to be in it. So Harold wanted to establish [himself] with the other celebrated Beats, with whom he belonged. That was clearly a priority.

I think that where you’re right is that he was always dipping into other channels. He believed in the accidents; he loved Surrealism and the divine inspiration of the haphazard.

I was already fully functioning by the time I met him. I was born in 1947 and didn’t meet Harold until I was 27. By that point I had been involved in the civil rights and anti-war movement, [arts scene in New York City’s] SoHo, I was up and going. Gerard Malanga thought that I would be the perfect partner for Harold. That was wrong.

He was extremely generous with his criticism and feedback; it was an extraordinary thing. Like most artists, I feel that a great deal of what’s necessary is shoveling away the bullshit. So: you find out who you are, then you work from that place if you can tell the truth, which is what he did in his work at his best. Harold told the truth, in his yearning and also his gutsy use of language.

He was extremely generous with his criticism and feedback; it was an extraordinary thing. Like most artists, I feel that a great deal of what’s necessary is shoveling away the bullshit. So: you find out who you are, then you work from that place if you can tell the truth, which is what he did in his work at his best. Harold told the truth, in his yearning and also his gutsy use of language.

At his best, he was shoveling away whatever obstructed a certain energy at its most crass. It could be a sexual frustration. On a higher level, it was this spiritual desire to participate in the life of culture.

As a teacher, there were two things that happened in his class. I’m not an intellectual or an academic, but his class was one of the most interesting things I’ve ever done as a writer. It was divided into two parts. One part was Harold giving a lecture about Modernism and how it began and came all the way through the 19th century, through Yeats and the Surrealists, all the way up to where we were in the 1970s. The point of that was to frame what we’re doing, all of us who write, in a larger context.

What Harold was doing was showing people– it was an amazing thing because his poetry was so personal, so much him…. What was great was that he could completely step out of any egotism and talk about poetry comprehensively. What is language? Why is poetry important? Why is language important? How do we discover who we are and what our culture is? What are the values that are living things, which we can hold on to?

Yes, recognition would have been nice. We’d all love it. He got some; he didn’t get enough. More important than that…

there is a force field in this country that followed Nagasaki and Hiroshima and it blew up with the Beats. We are still seeing the repercussions of that through the revolution of the 1960s, the sexual revolution and the liberation, thank God, of women and other minorities, now transgender people. Harold was so, so conscious that this transformative force was, also, the instrument by which we were being shaped and used.

As personal as he was, and as human as he was, as much himself as he was, he could also take a very long-range cultural look going all the way back to the Greeks and Romans, to Catullus and the people he translated, and come up through to modern times, with a great sense of fidelity to what was possible, through being an artist, as long as people were being honest. I don’t know what he would have done with a dishonest person.

Harold chose people to impart this sense of belonging to– you talk about family; he made us believe we were part of a family. It was an incredible thing because his mind was on that level, quite apart from ego. It was clear, like a prism. That shows through what he did in [his magazine] Bastard Angel too.

There was the historical element and then there was the welcoming of wildness.

There was the Apollonian and the Dionysian. I would say Harold would always come down on the Dionysian for himself, but that doesn’t mean he didn’t have a real sense of the Apollonian because he could feel it in inanimate objects even like unopened parcels. For example, saying: “That’s not going to be good. It’s shit.” [Audience laughs] He would know.

There were about twelve people in the class. It was in one room of his flat. It was about a three or four hour evening… every other week. I really wish it had been recorded because…

You know, I know more about painting than writing, so I always saw Harold as a kind of abstract expressionist like Franz Kline or Jackson Pollock in the way that he used his materials. How gutsy it was. His love and appreciation of the various branches of twentieth century art movements– cut ups, Surrealism, Dada– things that never appear in his work, to the best of my knowledge, like Tristan Tzara, and how that related to the Living Theater or the Angels of Light, which was an underground culture here in San Francisco.

Harold totally got how different groups of artists created their survival systems and then created, call it whatever you will, schools or movements or styles, which were their way of finding a tribe.

So he wanted that very much for himself and he appreciated it very much when other people had done it, sometimes under the aegis of people like the Steins in Paris, but in theater and painting and poetry.

He also had a profound appreciation for people like, at the most extreme, Emily Dickinson, although she wasn’t the subject of one of his lectures, who could only function within a very small bandwidth. It wasn’t a question of being out there; it was a question of the quality of the focus. Harold had a wonderful, generous way of appreciating how we got to where we are.

I think that, like most of the people in this room, he would feel horror at what we’re seeing out there now because it is so different than what he wanted for our country.

Adrian Brooks has a remarkable range of mind similar to that of Harold himself, and his recollection of Norse’s master class is priceless. Can we do something like this today? But who knows as much as Harold did today? Adrian himself would be great.